A murder happened in my village, and it led to a mass arrest.

In a village like mine, you were either related to some or most of the people: uncles, neighbours, cousins, your friend’s father, and all. Everyone who had their houses or farms close to the scene of the murder got arrested. Many of them would go on to be remanded in prison for years, and this made me want to become a lawyer.

I watched my father’s passion for helping people as I grew up in our local village in Ekiti State, Southwest Nigeria. He was quite educated, and as a chief, he was a community person. Like in all communities, things happened in our community. Disputes, issues, and a need for representation. He was sacrificial in how he represented and spoke up for his community, with absolute delight and joy.

As a young child, I saw all of that. It was not particularly rewarding. You know how they say, “A prophet is not respected in his own home”? I felt that truth. He didn’t expect to be rewarded, and I understood at that very early stage that success means impact, not necessarily prosperity.

I was in my junior secondary school when the murder happened. My father, as usual, was at the forefront of it. He was trying to help and see to their release. Our village is an hour and a half away from the state capital, Ado-Ekiti, and so we didn’t have access to lawyers. They needed lawyers and needed money as well. My father was always travelling to Ado-Ekiti in search of lawyers. Even when he got lawyers, there was no money to pay.

They didn’t commit any offense; the whole community knew this, but they ended up being incarcerated. It took two years before their eventual exoneration. During the period of their incarceration, the kids in the village would always ask, “When are they coming back home?”. The replies came with palpable helplessness “We don’t have lawyers, we can no longer pay the lawyers, we don’t know”.

The injustice seared itself into my heart: “Why don’t we have a lawyer in our village?” I asked myself. I was twelve at the time, and it was at this moment I decided I’d become one, not just to study law, but to fight for those who had no one. And you know that’s what every parent wants to hear, so they gave everything to help make it a reality.

In 2013, years later, I was called to the Nigerian Bar. After youth service in Akwa Ibom, I began practicing law in Lagos, but the problem I’d seen at twelve wasn’t confined to Ekiti—it was everywhere.

Fast forward to 2016, I visited Ikoyi Prison for the first time, and it broke me.

The stench hits first. Then the sights of about three thousand people crammed into a space meant for eight hundred. I knew I wasn’t going to leave here the same, both mentally and emotionally. The air was heavy, toilets few, and hope even scarcer. I listened to the stories of some of the inmates–from petty crimes, to wrong arrests, years stolen from them. I was torn between two paths: run for my mental health’s sake or become part of the change agents to fight to change this nightmare.

I chose to fight.

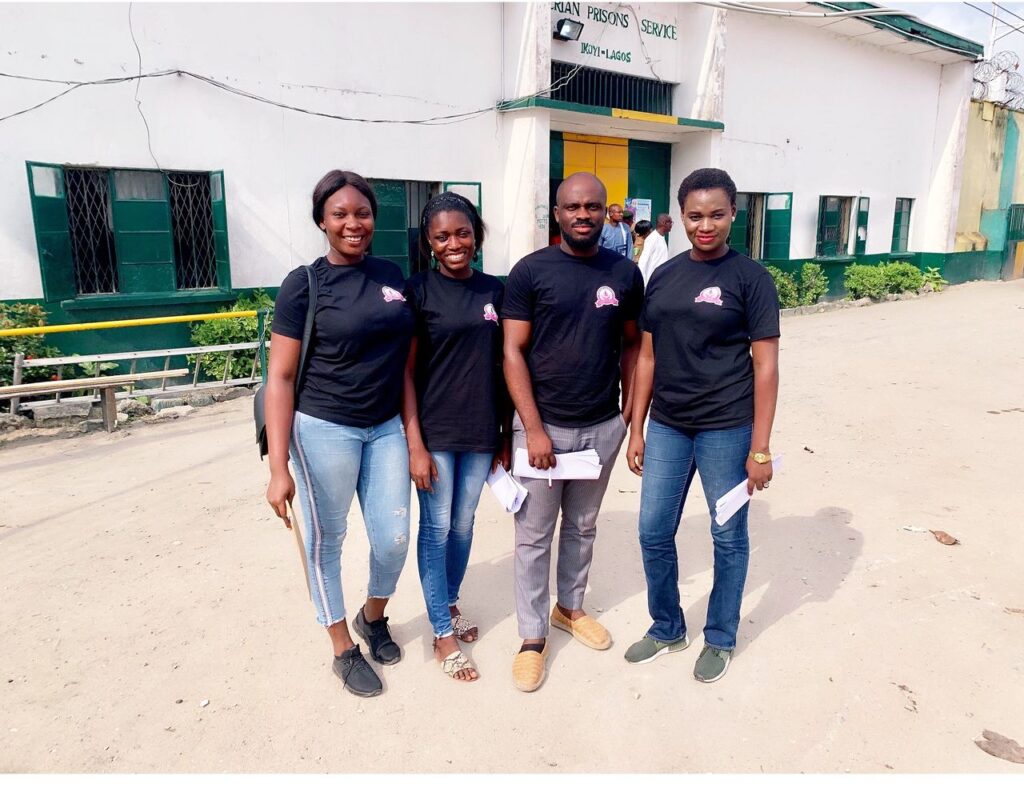

2019 was the year I founded Headfort Foundation for Justice, a nonprofit organization to provide access to justice and offer pro bono legal services. The organization was the product of the experiences with the Justice system I had witnessed up until that time. Specifically, the incident in my village in Ekiti and also my visit to Ikoyi prison. The first thing on my mind after the organization was founded in Lagos was expanding to Ekiti.

It wasn’t until 2021 that this opportunity came. A simple letter to the Chief Judge of Ekiti State got us approval and won us an office in the High Court of Ado-Ekiti. I had always said, “I practise in Lagos. I am Nigerian, but home is home anytime”. So on launch day, standing in my home state, I felt my twelve-year-old self exhale. We were finally here.

The prison in Ekiti was built for two hundred inmates, but when we visited, we realised it held over five hundred. We were there to offer medical aid to the Ekiti inmates. The drugs and tests we had planned for were for two hundred inmates–it wasn’t nearly enough, but it was a start.

I listened to the stories of the inmates. Every case hit close to home. I remembered a friend from my secondary school days at Federal Government Girls College (FGGC) in Kwara state. She was attending a FGGC in Ikole, Ekiti State. Her father was caught up as one of the victims of the mass arrest. He was the breadwinner of the family, and his absence forced her to drop out. It altered her life forever. One man incarcerated impacts thousands of people outside because most of them are the sole breadwinners of their families.

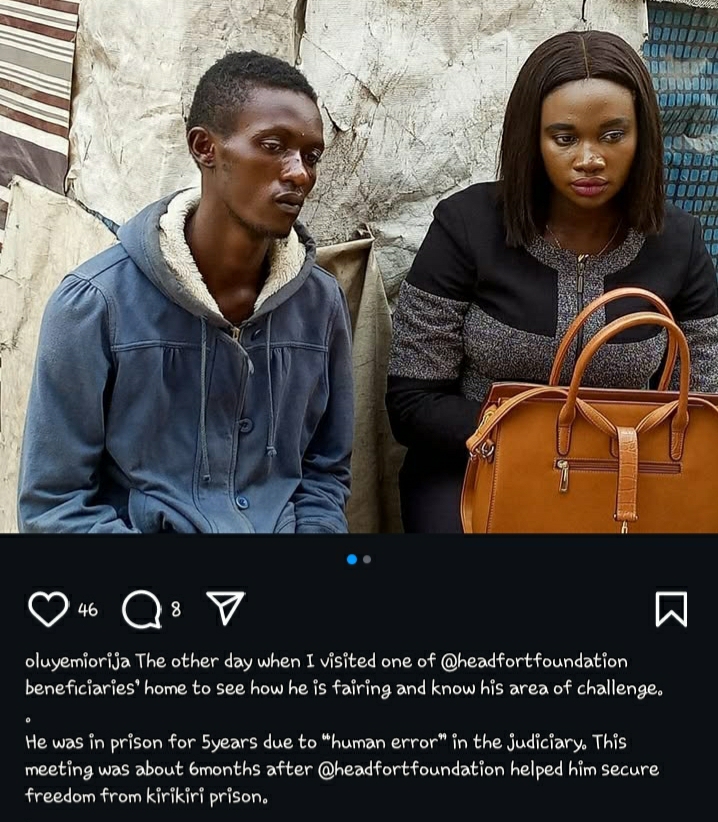

I’ve seen it firsthand, I know the impact of being incarcerated. It’s not just on them. They are the primary victims, but there are also secondary victims of incarceration. This makes me remember a motorbike rider I once represented, who was going home to his wife in labor. He was charged with armed robbery on that night.

He thought he had received the call that would change his life when he was notified that his wife was in labor. He was going home to take her to the hospital. On his way, he was stopped by a passenger who was headed his way, so he decided it wouldn’t hurt to make the extra cash on his way to his wife and soon-to-be-born child. On the way, he was stopped by the police, and after a routine search, the passenger was found carrying a weapon. They were both arrested and charged with armed robbery. He was illiterate, and his statement was written for him. In his statement, he “confessed” to being an armed robber and appended his thumbprint on it. He met his child at six years old, after six years behind bars. His wife found us through her pastor, and we helped secure his release. After six solid years!

A strong “why” keeps me going on the days I question myself and what I am doing. There are times I have been invited by the police and questioned as to why I represent the people I do. In one instance, I asked, “Which law says I cannot represent this person?” to which they replied, “This person is a criminal”. Even when no court of law has ascertained this? I say to myself. We also share compelling stories of the people we help out of prison. This is to teach people how the Nigerian Justice system works, and solicit support to help more people.

But these stories sometimes get us in trouble with the Nigerian Correctional Service. They think what we are doing is painting them in a bad light. I wondered if it was previously in a good light, and we are merely castigating them. It is not a revenue-generating agency, so the government is not very interested in what happens there. We share the stories to ensure the government sees them and does the needful to ensure the lives of the people in custody are safe.

The federal government and some state governments have some agencies, like the Legal Aid Council and the Office of the Public Defender (OPD) in Lagos State, that provide legal aid for Nigerians who need it but cannot afford it.

Here’s a scenario for why it is not so effective. A man, for instance, is picked up at a location far from the OPD or Legal Aid Council office. How will they know about these agencies? Even when their families are aware, they cannot afford to transport themselves to these offices to make a report. The only time the man comes across a lawyer is when he gets to court. At the police station level, which is the entry point to the justice system, they have no access to a lawyer. Also, the Nigerian police are underfunded, and things like writing a statement, making photocopies, and documentation have financial implications. It is said that “bail is free,” but the reality is that it is not.

Victims of police raids, who usually have done nothing wrong, are often extorted for money. If they have the money, they pay whatever they are asked to pay and go. But if they don’t pay, depending on which side of the bed the police officer woke up on, they are charged. The charge could be for armed robbery, petty theft, and if one is unlucky, they are given a felony charge, which they’d have to deal with for the next 5 to 10 years. A lot of the irregularities happen at the police station level, and the court cannot or might not be able to remedy it immediately.

The very first guy I helped out of prison was from Ikorodu. At the time of his arrest, he was a mechanic’s apprentice going to their workshop in the morning. The police were raiding that morning, and thirty people, including this young man, were arrested. Soon after, they were charged.

For cultism.

The ones who could bail themselves out did. The ones who couldn’t were charged to court. The number had reduced from about thirty to twenty-two as some had the money to make bail.

I met this young man at the prison during one of our visits. He came from Oyo state to Ikorodu to learn to be a mechanic. He had no family in Ikorodu or in Lagos to help perfect his bail. He was remanded for 6 months. We took up his case and represented him, but eventually the court struck out the matter as the police obviously had no evidence to prove that he and the remaining others were cultists.

Getting acquitted by a Nigerian court is like a favour has been done to you.

“You can now go home and meet your family”.

Even though a fundamental human right action can be taken, in cases of wrongful arrest and detention, once a Nigerian goes through the justice system, the majority are unwilling to go through it again. These civil suits demanding compensation can last for another year. Getting compensation from the police if such a suit is won is tough. Most people, when they hear the reality of the process and what it entails, are uninterested. I have witnessed scenarios where people had their cases struck out by the courts and were meant to go back to prison to pick up their personal items, like phone, belt, and clothes. One said to me, “I don’t even want to see the gate or remember what that place looks like”.

A lot of amendments have to be made to the law to make it easy for the police to pay damages. I even think it should be paid by the particular prosecuting officer, from his pension or salary, so they can be careful of the kinds of cases they prosecute.

In 2020, Nigeria had the EndSARS protest against police brutality. People were arrested for protesting or even being sighted close to areas of such protests. The prisons and police stations were filled up, both guilty and innocent. A lot of people needed legal services. The people who were socially exposed, on social media, were able to call for support and then got legal aid. My organization was also on the ground providing legal aid for people, going to police stations, and helping out. It was, however, hard for ordinary people who were not on Twitter, for example, to get help.

Up until last year, there were still people being released from police custody. Many people didn’t know how to call for legal aid. Eventually, when the police charged them, they were not charged for protesting. Random charges and crimes were slapped on them.

All of this helped us conceptualize “Lawyers Now Now”, a digital app launched in 2021, connecting people to pro bono lawyers instantly. It’s on the App Store and Play Store, with countless attorneys signed up. EndSARS was tragic, but it woke a generation up and gave us a tool to help thousands.

My own family feels the strain of the work I do. I’m a lawyer, but some days a less-than-perfect wife or mother. PTA meetings clash with court dates, and my son will ask, “Mom, why didn’t you come?” My husband supports me, but even he has moments of worry, asking why I’m home so late. Yet they’re proud—I was told my son brags in school, “Don’t mess with me, my mom will deal with you.”